Box Turtle Bulletin

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobbyPosts Tagged As: Daily Agenda

August 24th, 2016

The governing council of the United Church of Canada voted at a meeting in Victoria, British Columbia, to allow gay men and women to be ordained into the clergy. The church, which was formed in 1925 from a merger of Canada’s Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational churches, decreed: “All persons regardless of their sexual orientation, who profess faith in Jesus Christ and obedience to Him, are welcome to be or become members of the United Church. All members of the church are eligible to be considered for the ministry. All Christian people are called to a lifestyle patterned on Jesus Christ. All congregations, presbyteries and conference covenant to work out the implications of sexual orientation and lifestyles in the light of Holy Scriptures.”

The final report approved by the governing council added: “we confess before God that as a Christian community we have participated in a history of injustice and persecution against gay and lesbian persons in violation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” It also acknowledged “our continued confusion and struggle to understand homosexuality.”

The 205-160 vote followed months of heated debate, during which a quarter of the church’s ministers and 30,000 of its 860,000 members signed a declaration opposing the move. Over the next four years, membership fell by 78,000 as some congregations split and a few others left the denomination altogether.

August 24th, 2016

(d. 1990) His tiny hometown of Gary, South Dakota, straddling the state line with Minnesota, may have been off the beaten path, but the town’s only newsstand was located in his father’s drugstore, providing young Chuck with a window to a much larger world. He vividly remembered that day when he snatched a copy of Sexology magazine, a small quasi-scientific magazine about the size of a Reader’s Digest, and read “that if one was homosexual, he shouldn’t feel strange or odd, that there were millions of us, that there was nothing wrong with it.” Rowland knew from the time he was ten years old that he was gay, when he fell in love with another boy. “As soon as I read that there were millions of us, I said to myself, well, it’s perfectly obvious that what we have to do is organize, and why don’t we identify with other minorities, such as the blacks and the Jews? I had never known a black, but I did know one Jew in our town. Obviously, it had to be an organization that worked with other minorities, so we would wield tremendous strength.” Organizing would become Rowland’s greatest contribution to the early gay rights movement.

In the late 1930s, Rowland went to the University of Minnesota where he met Bob Hull (May 31), and the two became lovers, briefly, and then lifelong friends. Rowland was drafted into the Army, but thanks to a severe injury he stayed stateside and, “frankly, I had a ball.” After his discharge in 1946, he became an organizer for the New York-based American Veterans Committee, a liberal veterans group. Rowland also became friends with a young man whose parents had been Communists. Rowland decided to join the Communist Party and became head of a youth group called the American Youth for Democracy in the Dakotas and Minnesota. He left in 1948, “not because I disagreed with anything, but because I just wanted out. Joining the Communist Party is very much like joining a monastery or becoming a priest. It is total dedication, twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year.”

That year, Rowland moved to Los Angeles to start a new life. Hull soon followed and the two of them met Harry Hay (Apr 7), who was already kicking around with the idea of starting an organization for homosexuals. Rowland and Hull, along with Dale Jennings (Oct 21), met with Hay and Hay’s lover, Rudi Gernreich (Aug 8), and in November of 1950 they formed what would become the Mattachine Foundation (Nov 11). Rowland’s organizational skills to be an important asset to the fledgling group. Given the fearful political climate of the McCarthy era, Mattachine meetings were held in secret, with members using aliases and the leadership known only as “The Fifth Order.” Taking a cue from the Communist party, each discussion group or chapter was operated autonomously with loose coordination, so that if police were to raid and arrest the members of one chapter, it wouldn’t endanger the others.

An exceptionally rare photo of early members of the Mattachine Society. Pictured are Harry Hay (upper left, Apr 7), then (l-r) Konrad Stevens, Dale Jennings (Oct 21), Rudi Gernreich (Aug 8), Stan Witt, Bob Hull (May 31), Chuck Rowland (in glasses), Paul Bernard. Photo by James Gruber (Aug 21). (Click to enlarge.)

That worked for a while. But by 1953, Mattachine had grown to over 2,000 members, thanks in part to the publicity over Dale Jennings’s acquittal of trumped up charges for soliciting a police officer (Jun 23). Mattachine raised its profile during the trial: raising money, hiring a lawyer, and generating quite a bit of publicity along the way. But the flood of new members brought pressure to change the Foundation. In particular, they demanded the secrecy surrounding the leadership’s identities be abandoned and the organization cleared of Communists. Many of them also demanded that the Foundation become less “activist,” an ironic stance given that Mattachine’s activism in the Jennings case was what made the newer members aware of the organization in the first place.

The group also split over a far more fundamental disagreement: over the nature of homosexuality itself. Were they a distinct cultural minority seeking recognition, or were they exactly like heterosexuals in every way except one? The latter “integrationist” model was sought by many (though certainly not all) of the more “conservative” members, who also demanded transparency, the ejection of former Communists, and a non-confrontational approach to public activism. A Constitutional Convention was called to try to reconcile the many emerging fault lines and come up with a new organizational structure that everyone could agree on (Apr 11). Rowland gave a speech which blasted through the wall of secrecy of the group’s leadership. “You will want to know something about the beginnings of the Mattachine Society, how the Fifth Order happened to be. … I think it is reasonable that you should ask this and important that you understand it,” he said. He then introduced the leadership to the rank-and-file. That satisfied one of the conservatives’ demands. But he also declared his unwavering belief that homosexuals were a unique, valuable segment of society, and if they could only see themselves as such, and with pride, only then could they effect change in society. “The time will come when we will march arm in arm, ten abreast down Hollywood Boulevard proclaiming our pride in our homosexuality.” The newer members found that idea far too radical and confrontational — and downright “communistic.”

Rowland proposed a new constitution, organizing the Mattachine Foundation as a group of autonomous clubs governed by a committee and an annual convention. His draft constitution was rejected and the convention decided to suspend its meeting due to a lack of consensus. During a second meeting called for May, Rowland, Hull and Hay resigned their leadership positions, the remaining members declared the Mattachine Foundation disbanded, and announced the formation of the newly reconstituted Mattachine Society with a centralized organizational structure and a disavowal of activism.

Rowland tried to remain active in the new Society, in a chapter that was intended to take on legal cases. But an attorney for the new Society charged that “the very existence of a Legal Chapter, if publicized to society at large, would intimidate and anger heterosexual society.” At the next convention in November, Rowland’s chapter was shut down, Rowland himself was branded a Communist, his credentials were revoked and he was out of the group.

Meanwhile, a group of disaffected Mattachine members had founded ONE, Inc. (Oct 15), which was originally formed solely to publish ONE magazine, but which found itself fielding questions and requests for help from gay men and women who were showing up at its tiny Los Angeles office. Rowland became director of ONE’s social services division, providing job placement and counseling services for nearly 100 people in 1955 alone. The following year, Rowland decided to found a church, the Church of One Brotherhood, using the name he lifted from ONE. The church launched a burst of activity in social work, activism and advocacy before flaming out in 1958.

Soon after, Rowland began suffering from alcoholism, had a nervous breakdown, saw a business partnership go belly-up, went into debt, and was evicted from his home. When Hull committed suicide in 1962, Rowland decided it was time to start over. He moved to Iowa where he somehow managed to become a high school teacher. He then earned his master’s degree in theater in 1968 and chaired a theater arts department at a Minnesota college. On retiring in 1982, Rowland returned to Los Angeles to form Celebration Theatre, “the only theatre in Los Angeles dedicated exclusively to productions of gay and lesbian plays.”

In March of 1990, Rowland was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer. He moved to Duluth, into an apartment donated by a former student, and spent the remainder of his days among students and relatives. He died on December 20, 1990.

August 24th, 2016

Fry never really had an official coming out moment in his professional life. When he was asked when he first acknowledged his sexuality, Fry joked, “I suppose it all began when I came out of the womb. I looked back up at my mother and thought to myself: ‘That’s the last time I’m going up one of those.'” His early interests included being expelled from two schools and spending three months in prison for credit card fraud. But once he got that behind him, he earned a scholarship to Queen’s College at Cambridge where he was awarded a degree in English literature. While at Cambridge, he joined the Cambridge Footlights, an amateur theatrical club, where he met his best friend and comedy co-conspirator Hugh Laurie.

After a Cambridge Footlights Review in which Fry appeared was broadcast on television in 1982, Fry and Laurie were signed to two comedy series for Granada Television. In 1983, the duo moved to the BBC. Their first show, a science fiction mocumentary, flopped and was cancelled after only one episode. Their next project, the sketch comedy A Bit of Fry & Laurie, was considerably more successful, running for four seasons between 1986 and 1995. Fry also appeared in several episodes of Rowan Atkinson’s Blackadder series.

Beginning in 1992, Fry began appearing in several BBC dramas, and in in 2005 he added documentaries to his many projects. He explored his bipolar disorder in the Emmy Award-winning Stephen Fry: The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive in 2006, and that same year he delved into his genealogy in an episode of Who Do You Think You Are? His six part 2008 series Stephen Fry in America had him travelling through all fifty states, mostly in a London Cab. His film credits include portraying Oscar Wilde — a role he said he was born to play — in 1997’s critically acclaimed Wilde. He made his directorial debut in 2003’s Bright Young Things, and he provided the voice for the Cheshire Cat in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland.

Fry’s interests seems to know no bounds. He’s appeared in London’s West End, published four novels and several non-fiction works, and sat on the board of directors of the Norwich City Football Club from 2010 to 2016. He flies his own biplane, and is a member of the Noel Coward Society, the Oscar Wilde Society, the Sherlock Holmes Society — and he was was voted pipe-smoker of the year in 2003.

He is also an advocate for mental health, based on his own struggles with bipolar disorder and thoughts of suicide. In 2013, he revealed that while filming abroad for a BBC documentary, “I took a huge number of pills and a huge [amount] of vodka.” The mixture made him convulse so much that he broke four ribs. “It was a close-run thing,” he said. “Fortunately, the producer I was filming with at the time came into the hotel room and I was found in a sort of unconscious state and taken back to England and looked after.” That documentary Fry was filming, “Stephen Fry: Out There” aired on BBC 2 in November 2013, and it featured him confronting anti-gay campaigners in Russia, Uganda and elsewhere around the world, as well as ex-gay movement leaders in the United States. He married comedian Elliot Spencer in 2015

August 23rd, 2016

Twenty-nine year old Morris Levy used his fortune from Roulette Records, which he had founded in 1956, to buy Roundtable two year later when the previous owners racked up a $750,000 tax bill. Before Levy bought, renovated and renamed it, the club had been the Versailles, which for the previous twenty-two years was regarded as one of the finest restaurant/cabarets in the world. Levy turned the Roundtable into a restaurant and jazz club featuring several major acts. It was also a rather convivial place, with Steve Allen stopping in to take a spin at the piano and Jackie Cooper joining him on drums from time to time. By about 1970, jazz had departed the Roundtable, and the stage and dance floor area was given over to the gays, and a few years after that the Roundtable jumped on the disco bandwagon. GAY, the nation’s first weekly gay newspaper, said in 1971 that the Roundtable was “like dying and going to heaven.

August 23rd, 2016

In the two years following the seminal Stonewall Rebellion, a new wave of gay advocacy and visibility broke over the landscape, going far beyond anything that had gone before. Straight America was scratching its collective head: where did all of these homosexuals come from? They seemed to be everywhere — holding hands in Greenwich Village, running for student presidents at major universities, and marching in the streets shouting something about “gay pride.” Newsweek devoted four pages trying to explain it all to its readers:

To supporters of gay liberation, marching in the streets and holding hands in public are only minor gestures of assertion. They are picketing the Pentagon, testifying at government hearings on discrimination, appearing on TV talk shows, lecturing to Rotary Clubs, organizing their own churches and social organizations and, perhaps most important of all, using their real names. “Two or three years ago, a homosexual who tried to explain what he and the gay movement were all about would have been ridiculed,” says Troy Perry, a homosexual minister who established Los Angeles’s Metropolitan Community Church in 1968 and has been a movement hero ever since.

…What seemed then it relatively minor clash is now enshrined in gay-lib lore as the “Stonewall Rebellion.” Within weeks, the first of scores of militant homosexual groups, the Gay Liberation Front, was formed in New York. The new mood quickly crossed the continent, leading to the creation of similar organizations in Los Angeles and San Francisco. By the first anniversary of the Stonewall incident, the militants were on the march in a dozen cities. By the second anniversary, they were celebrating Gay Pride Week with an elaborate panoply of parades and protests. The movement already has a book-length history in print and some of its more imaginative propagandists have even begun to speak of a “Stonewall Nation.”

Virtually the entire four-page article dealt with the sudden visibility of the gay community — a visibility which had personal, psychological, familial and political aspects, according to Newsweek. As one measure of the surprise this new openness must have engendered, the word “militant” appeared in the four-page article fifteen times. And what the authors regarded “militant” is revealing: they described “militants” coming out to their friends, families and employers; “militants” wanting acceptance; “militants” refusing to accept the APA’s verdict that they were mentally ill (the APA would set aside that verdict two years later); “militants” demanding an end to the ban on federal employment; “militants” starting gay churches and “militants” getting married in them, and “militants” saying it’s great to be gay. And that last thing, according to Newsweek was especially dangerous:

What all this suggests is a central problem that gay liberation usually chooses to ignore: if the movement succeeds in creating an image of “normality” for homosexuals in the society at large, would it encourage more homosexually inclined people — particularly young people — to follow their urges without hesitation? No one really knows for certain. Dr. Paul Gebhard, the distinguished anthropologist who directs the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, believes that gay lib “will not convert heterosexuals into homosexuals but might encourage those who are going in a homosexual direction to feel less guilty about it.” New York sociologist Edward Sagarin takes an even dimmer view. “If the militants didn’t say that it is great to be gay,” Sagarin insists, “more adolescents with homosexual tendencies might seek to change instead of resolving their confusion by accepting the immediate warm security that tells them they are normal.”

A sharp-eyed reader may recognize Edward Sagarin’s name. A decade earlier, he used to be a regarded as the influential “Father of the Homophile Movement,” writing under the pseudonym of Donald Webster Corey. Sagarin might have been a towering gay rights figure if he hadn’t turned against the very movement he inspired (Sep 18). Three weeks later, gay rights advocate Frank Kameny (May 21), who undoubtedly felt a personal responsibility to respond to the man who had once inspired him to advocate for gay rights, challenged that paragraph with this letter to the editor:

The gay liberation movement has been formulating its positions for some twenty years, has quite “come to grips with all the implications of its own positions” and does not at all “choose to ignore” the “problem” of “more homosexually inclined people — particularly young people — [following] their urges without hesitation.” Not only do we consider this neither a problem nor a danger; we consider it an eminently desirable goal to be worked toward and achieved as soon and as fully as possible. It is the very essence of liberation.

August 22nd, 2016

August 22nd, 2016

(d. 1989) With both parents as silent film stars and his father a director, it should surprise no one that the future author and Pulitzer prize-winning playwright would begin his career as an actor. In 1953, on the CBS soap opera Valiant Lady, Kirkwood played the title character’s son, Mickey Emerson. The fifteen minute program was a noontime fixture for four years, broadcast daily from New York. You can see one complete episode here, complete with organ music and commercials. (“Mickey” makes his appearance at 5:24, but you won’t want to miss the melodrama preceding that scene.) Kirkwood stayed on the series for its entire run through 1957.

(d. 1989) With both parents as silent film stars and his father a director, it should surprise no one that the future author and Pulitzer prize-winning playwright would begin his career as an actor. In 1953, on the CBS soap opera Valiant Lady, Kirkwood played the title character’s son, Mickey Emerson. The fifteen minute program was a noontime fixture for four years, broadcast daily from New York. You can see one complete episode here, complete with organ music and commercials. (“Mickey” makes his appearance at 5:24, but you won’t want to miss the melodrama preceding that scene.) Kirkwood stayed on the series for its entire run through 1957.

James Kirkwood and Nancy Coleman in Valiant Lady

That Kirkwood’s debut should be on Valiant Lady is appropriate since already in his young life he had experienced more twists and turns than could be portrayed on any soap opera. His parents’ careers were already fizzling by the time he was born, and the millionaire couple was soon flat broke. They divorced when he was seven after his mother left the family. Biographer Sean Egan, author of Ponies & Rainbows: The Life of James Kirkwood, writes that the younger Kirkwood stumbled upon the dead body of his divorced mother’s fiancée when he was twelve, endured kamikaze attacks when serving in the Coast Guard during World War II, and befriended Clay Shaw, the only man to be put on trial in connection with the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

With all of that going for him, it’s no wonder he decided to try his hand at comedy. His first semi-biographical novel, There Must Be A Pony! was based on the scandal surrounding his mother’s dead fiancée. Another novel, P.S. Your Cat Is Dead was turned into a stage play and a film by Steve Guttenberg. Kirkwood’s crowning achievement was the book he co-wrote with Nicholas Dante for A Chorus Line, which earned him a Tony Award, a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Book of a Musical, and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1976. He also wrote the comedy Legends! which toured the U.S. with Mary Martin and Carol Channing in 1987, and was revived in 2006 starring Joan Collins and Linda Evans. But for the most part, the fame from A Chorus Line proved to be more of a distraction than a boost, and the last fourteen years of his life were more notable for his unproduced screen plays, stage projects, and the epic novel about his father that he never finished. Kirkwood died of spinal cancer in 1989.

August 21st, 2016

August 21st, 2016

50 YEARS AGO: Stonewall gets all of the press. Lore has it that it is the very first time in modern history that the LGBT community physically fought back against police harassment. Lore is wrong.

50 YEARS AGO: Stonewall gets all of the press. Lore has it that it is the very first time in modern history that the LGBT community physically fought back against police harassment. Lore is wrong.

Until some very recent development began to take hold in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, it has always been an impoverished neighborhood, home to the transient and the marginalized. Polk Street, between Ellis and California Streets, was the heart of the gay community in the 1960s. Turk Street, to the south and east, was home to the transgender/transsexual community. Because cross-dressing was illegal in San Francisco, gay bars often didn’t welcome transgender and transsexual people out of fear of being raided by police. What’s more, and because it was extremely difficult for transwomen to hold a job, many of them turned to prostitution and drugs. Rounding out the Turk Street population was a host of homeless LGBT youth, drag queens, prostitutes and hustlers.

At the corner of Taylor and Turk streets stood Gene Compton’s Cafeteria, a twenty-four hour restaurant and one of the few places that the people of Turk Street could go to get out of the weather and the violence on the street, and get a cheap meal or grab a cup of coffee between tricks. It was also the meeting place for Vanguard, a radical queer youth group established by Glide Memorial Methodist Church.

In the Spring of 1966, new management arrived at Compton’s, and they began to make life difficult for the hustlers, transwomen and homeless youth who spent a lot of time there but very little money. By summertime, Compton’s hired security guards and began calling the police to clear out the restaurant. Vanguard responded with a picket on July 18, but Compton’s policy of harassment and discrimination continued.

Then one night sometime in August — nobody knows when, and disturbances in the Tenderloin were so common that newspapers rarely bothered to report them — Compton’s again called the police to clear out the restaurant. When police arrived, One of the officers grabbed a transgender customer who threw her coffee in his face. Immediately, about fifty other customers started rioting, overturning tables, throwing dishes and breaking the cafeteria’s plate glass windows. The rioting expanded out in the street as customers left the cafeteria only to find more police officers and waiting paddy wagons. The riot only grew from there. By the time the night was over, one police car was destroyed and a corner newsstand was set on fire.

While little is known about the Compton’s riot, it did manage to have a lasting impact. The transgender community began organizing and police started backing off from arresting anyone violating the city’s cross-dressing laws. Those laws were eventually discarded a few years later. In 1968, the National Transsexual Counseling Unit was formed which brought together a network of social, psychological and medical support services for the transgender community. The NTCU was headed by Sergeant Elliot Blackstone, who had acted as a San Francisco Police liaison to the LGBT community since 1962.

Compton’s, like Stonewall, not the first time LGBT people fought back against police harassment. There had been a similar riot in 1959 at Cooper’s Donuts in Los Angeles. But the Compton’s riot was an important turning point. And yet it was almost forgotten. The 2005 documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria revived attention to the Compton’s riot once more, and a memorial plaque was set in the sidewalk in front of where Compton’s once stood ni 2006. The location is now a free clinic for women. The plaque reads:

Here marks the site of Gene Compton’s Cafeteria where a riot took place one August night when transgender women and gay men stood up for their rights and fought against police brutality, poverty, oppression and discrimination in the Tenderloin: We, the transgender, gay, lesbian and bisexual community, are dedicating this plaque to these heroes of our civil rights movement.

Here is the trailer for Screaming Queens:

August 21st, 2016

(d. 1898) He struggled with tuberculosis from the age of nine until his untimely death at the age of twenty-five. The nearly constant reminders of mortality may well have influenced his black ink sketches, which combined the then-popular whimsy of art nouveau stylings with grotesque themes (sometimes including depictions of enormous genitals and breasts) akin to what you might find in modern goth. “I have one aim — the grotesque,” he once said. “If I am not grotesque I am nothing,” Beardlsey received his first commission in 1893, when he published 300 illustrations for an edition of Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur. That same year, he was hired to create the illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome. Other notable works followed, for an edition of Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1896), a private edition of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata (1896) and his own A Book of Fifty Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley (1897).

An illustration for a privately published edition of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata (1896).

He founded the magazine The Studio in 1893 and co-founded The Yellow Book in 1894. The Yellow Book quickly earned a reputation for being provocative and daring, despite publisher John Lane’s constant attempts to keep Beardsley under control. Before each publication, Lane would painstakingly examine each of Beardsley’s illustrations to make sure he didn’t hide any inappropriate details, as Beardsley was known to do. The two played this cat-and-mouse game throughout Beardsley’s tenure at The Yellow Book, which shocked critics for his open mocking of Victorian values. In response to those critics, Beardsley published two drawings in one issue of The Yellow Book which were stylistically different from his other work, under the pseudonyms of Phillip Broughton and Albert Foschter. A critic at The Saturday Review called “Broughton’s” illustration “a drawing of merit” and Foschter’s “a clever study”. But as for Beardsley’s, they were “as freakish as ever.”

Beardskey was fired due to his association with Oscar Wilde soon after Wilde’s arrest in 1895. The Yellow Book‘s quality and popularity suffered, and it folded in 1897. Beardsly then went to The Savoy, where he also served as editor, allowing him to pursue writing as well as illustration. The Savoy was published by Leonard Smithers, a friend of Wilde who also published a number of Beardsley’s works, as well as, among other things, pornographic books. The Savoy lasted only a year. In 1897, Beardsley’s health deteriorated. He moved to the French Riviera, converted to Roman Catholicism, and died at the age of twenty-five on March 16, 1898.

August 21st, 2016

(d. 1997) Born the oldest twin, in Pasadena, California, Don Slater never did take to his father’s passion for team sports, but he did become an accomplished skier and swimmer and was passionate about nature and the outdoors. He also, early on, acquired an easiness among a variety of people, from street hustlers and cross-dressers to literature professors and librarians, which belied his conservatism — a “gentleman’s conservative,” friends called him.

While attending the University of Southern California in 1944 following his honorable discharge from the army, he quickly connected with the University’s “gay underground.” He met his partner, Tony Reyes, in 1945, and the two remained together for the next fifty-two years until Slater’s death. In the early 1950s, Slater and Reyes attended a Mattachine meeting in Los Angeles, but Slater found the whole thing silly. He was put off by the “mystic brotherhood” talk and dismissed the whole affair as “a sewing circle” and “the Stitch and Bitch club.”

But when he learned that Bill Lambert (a.k.a Dorr Legg, Dec 15), Dale Jennings (Oct 21); and others were about to found ONE Magazine as the first national publication for the emerging gay community (Oct 15), Slater felt that he found his calling. The first meetings of the nascent magazine took place in 1952 just before Slater’s graduation from USC (a graduation delayed by a bout of rheumatic fever) and those meeting minutes were written in his spiral class notebook.

Slater saw ONE’s main mission as being an educational one. When ONE, Inc., established an Educational Division, he became an Assistant Professor for Literature. He also became the organization’s archivist, which he saw is ONE’s core strength. Those duties were in addition to his role as an editor for the magazine. As the organization grew, Slater took on leadership roles on the Board of Directors. By the mid-1960s, a bitter dispute divided the board, and Slater led a group that complained that the board had been illegally usurped by the rival faction. In April of 1965, Slater, Reyes and Billy Glover moved ONE’s library and office from Venice to a new location on Cahuenga Blvd “for the protection of the property of the corporation.” For four months, confused subscribers received two competing ONE Magazines in the mail, one published by ONE, Inc., and the other by Slater’s The Tangent Group, named for a regular column in ONE.

Slater soon changed the name of his magazine to Tangents, but the dispute continued. The remnant faction at ONE, Inc., demanded the return of the archives, which Slater believed would have been threatened if they were returned. “If ONE has any assets, this is it. Damn the future of its publications, but the fate of this material is important.” After a two year court battle, the two sides settled, with ONE, Inc., retaining the right to publish ONE magazine and The Tangent Group retaining ownership of Slater’s beloved archives. In 1968, the Tangent Group re-incorporated as the Homosexual Information Center (HIC).

The turmoil over ONE did little to slow Slater’s activism. He helped organize a motorcade protest in Los Angeles in 1966 on Armed Forces Day to protest the exclusion of gays in the military, and he was arrested by police in 1967 when they shut down a play sponsored by HIC. In 1968, he led a picket of the Los Angeles Times for refusing to publish an ad for another gay-themed play. He continued to publish Tangents until 1973. Slater passed away in 1997 from rheumatic heart valvular disease. His HIC archives of more than 4,000 books, periodicals and pamphlets are now housed at the Vern and Bonnie Bullough Collection at California State University at Northridge.

August 21st, 2016

(d. 2011) James Gruber was born on Des Moines, Iowa. His father, a former vaudeville performer turned music teacher, moved the family to Los Angeles in 1936. In 1946, Gruber turned eighteen and enlisted in the Marines. He later remarked that being in such close proximity to men, he “went bananas in the sex department.” Despite the, ah, camaraderie, he continued to have affairs with women, and throughout his life he considered himself bisexual. After he was honorably discharged in 1949, he studied English Literature at Occidental College and met Christopher Isherwood, who would become a close friend and mentor.

In April 1951, Gruber and his boyfriend, photographer Konrad Stevens, became the last new members of a group of gay men who had begun gathering under the name of “Society of Fools,” which proved to be a turning point. “All of us had known a whole lifetime of not talking, or repression. Just the freedom to open up … really, that’s what it was all about. We had found a sense of belonging, of camaraderie, of openness in an atmosphere of tension and distrust. … Such a great deal of it was a social climate. A family feeling came out of it, a nonsexual emphasis. … It was a brand-new idea.”

An exceptionally rare photo of early members of the Mattachine Society. Pictured are Harry Hay (upper left, Apr 7), then (l-r) Konrad Stevens, Dale Jennings (Oct 21), Rudi Gernreich (Aug 8), Stan Witt, Bob Hull (May 31), Chuck Rowland (in glasses, Aug 24), Paul Bernard. Photo by James Gruber. (Click to enlarge.)

Gruber and Stevens brought a new sense of urgency into group, with Gruber suggesting the group rename itself the Mattachine Foundation, referring to the medieval masque troops known as “matachines” (spelled with one “t”). Gruber was also responsible for taking the only known photo of the early members of the highly secretive group when he snapped a quick snapshot during a gathering in 1951. Founder Harry Hay was furious that the members’ faces were photographed in violation of Mattachine’s strict policy of anonymity, and Gruber was nearly expelled. The only way he stayed in was by lying and saying there was no film in the camera.

Gruber was active in Mattachine’s early public push to address ongoing harassment the Los Angeles police department. He and other Mattachine members formed the Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment to raise funds for Dale Jennings’s solicitation trial (Jun 23). Gruber wrote and distributed much of Mattachine’s early literature to publicize the trial and solicit funds for legal fees. Not only did Jennings win his case, but Mattachine’s newfound public profile attracted a crop of new members. Ironically, those new members, having discovered Mattachine because of its publicity, demanded that Foundation pull back from the spotlight over fears of further harassment. Many of them just wanted was a social organization, not a political one. They also had misgivings over co-founder Harry Hay’s Communist connections. Frustrated over the looming takeover by the newer members, Gruber and the rest of the old guard resigned (Apr 11).

Gruber moved to San Francisco, and then Palo Alto, where he started going by the name of John. “It was the most effective way I could find to escape Mom’s ceaseless calling for ‘Jimmy!’ inside my head,” he said. He became a high school and college teacher, and he loved working in his new profession. In the late 1990s, Gruber became involved with documenting the history of the gay community and was recognized as a pioneering organizer. Before he died peacefully in 2011 at his home in Santa Clara, he was the last living member of the original Mattachine Foundation.

August 20th, 2016

The Exile was a popular Country and Western bar in downtown Washington, D.C. operated by the same owners who operated the D.C. Eagle. Both the Eagle and Exile, which were located just a couple of blocks from each other, have been displaced by downtown redevelopment. There had been plans to revive both clubs in a new location, but only the Eagle managed to reopen.

August 20th, 2016

The following letter to the editor appeared in the September 1953 issue of ONE magazine:

A Reply to R.L.M. in your JULY issue, AS FOR ME:

Who is in a position in this world to require conformity from anyone?–least of all one homosexual from another. The desire to have all homosexuals well mannered, intelligent, courageous, manly, men is easily understood. These are attributes most of us classify as desirable; most humans do, according to the standards of their own society. Is it not the aim of all persons in this country to attain both a personal integrity and equal rights before the law of our society? We as reasonably enlightened, 20th Century individuals are not in any position to slap the bar-fly or to condemn bar-flitting; promiscuity to us is a personal matter; emasculated affectation is neither my concern nor another’s. The so called “gay life” is not for me to reform and I hesitate to define the “very worst elements”.

No! If we must have a crusade it must be for civil rights and equality before the laws of this land, not for conformity to some ideal of personal ethics. I do not care how many “gay” bars exist or who goes to them or what they do there, who delights in emasculated affectation or uses perfume; but I do care that my rights as a citizen of this country are nil and I know that getting all homosexuals to act like bourgeois gentlemen is not going to get those rights for me. I am not sure what will but I think ONE may be on the right track.

RENO, NEVADA

August 20th, 2016

ONE magazine, August 1953.

The push for marriage equality has often been measured in years. Some of the more amazingly short-sighted have asserted that “the revolution began” when Prop 8 was challenged in Federal District court in 2009. Others with somewhat longer memories can remember the excitement of Massachusetts becoming the first U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage in 2004 (May 17), or the Netherlands becoming the first country in the world to offer marriage equality in 2001 (Apr 1), or Hawaii almost becoming the first jurisdiction to allow same-sex marriages in 1993 (May 5). Those with longer memories may recall the battle Mike McConnell and Jack Baker waged to get a marriage license in 1970 (May 18).

Discussions about same-sex marriage had taken place in the gay community long before all of that. ONE magazine, the nation’s first nationally-distributed gay publication, had called for a push for “homophile marriage” in 1963 (Jun 20). In 1959, ONE published “Homosexual Marriage: Fact or Fancy?” Its author had been in a relationship for eleven years which he very much likened to a marriage, and proceeded to offer advice on the ingredients that made for a successful marriage. But with gay relationships themselves still criminalized throughout much of the U.S. and the mental health professions considering homosexuality a mental illness, marriage was considered a much lower priority.

ONE‘s first discussion of gay marriage came in its very first year of existence, in 1953. Written by a ONE reader who signed his name “E.B. Saunders,” the article’s title, “Reformer’s Choice: Marriage License or Just License?”, predicted the tug-of-war between assimilationists and liberationists that would dominate the gay rights movement for the next half century. It also records some of the pre-pill/pre-sexual revolution/pre-women’s liberation-era assumptions about what was considered acceptable behavior. Overall, it’s a fascinating time capsule, left by of a group of people who were still trying to figure out who they were and what they wanted.

The activists in the early homophile movement believed they knew what they wanted. First and foremost, ONE and the Mattachine Society wanted to reform anti-gay laws criminalizing gay relationships in all fifty states. That word, reform, was carefully chosen so as not to draw the charge that they were encouraging people to adopt what was seen as an immoral lifestyle. To speak boldly of repeal during those years following the Lavender Scare would have been, politically, like touching a third rail. The backlash, it was feared, would have been devastating. But the reason ONE and Mattachine wanted those laws reformed was obvious: they wanted people to no longer face arrest for having homosexual sex. This made gay people among the earliest proponents of sexual liberation — or sexual “license,” depending on your viewpoint.

ONE and Mattachine also wanted the “acceptance” of gay people, a goal they sought to achieve by educating the broader society of the “homosexual’s problems.” But Saunders wrote that if ONE and Mattachine really wanted society’s acceptance, then their efforts would be doomed unless they adopted an agenda that included the one thing that society found most worthy of acceptance: marriage.

…Then you sit back and try to visualize our society as these well-meaning enthusiasts would have it. And suddenly you realize that their plans are impossible! They have missed one of their most essential points and committed a basic and staggering error.”

…Image that the year were 2053 and homosexuality were accepted to the point of being of no importance. Now, is the deviate allowed to continue his pursuit of physical happiness without restraint as he attempts to do today? Or is he, in this Utopia, subject to marriage laws? It is a pertinent question. For why should he be permitted permiscuity (sic) when those heterosexuals who people the earth must be married to enjoy sexual intercourse? The answer does not lie in the fact that the deviate cannot reproduce: this is irrelevant to the effect upon society of his acceptance as a valuable citizen.

This effect would be one of immense consternation for it would be a legalizing of promiscuity for a special section of the population — which, incidentally, now begs for its rights on the very grounds that it desires the respectability and dignity of all other citizens. It is not likely that either of these would be attained by a lifting of legal sex constraints for this group alone. Actually such a change would loosen heterosexual marriage ties, too, and make even shallower the meaning of marriage as we know it… Heterosexual marriage must be protected. The acceptance of homosexuality without homosexual marriage ties would be an attack upon it.

Let’s pause a minute and let this amazing point sink in. Saunders is saying — in 1953! — that acceptance of gay people without letting them marry (or, more to the point expecting them to marry; this is, after all, 1953) would be an attack on straight marriages.

Saunders obviously overstated the constraints marriage placed on people’s behavior, as the Kinsey Reports of 1948 and 1953 had already shown (Jan 5, Aug 14). A large number of married people were already findings a large number of ways to be promiscuous. Marriage did little to lessen the constraints of sex, legally or otherwise. But if gay people really wanted to be accepted, then Saunders argued that they should be fighting for the one thing that would open the doors to acceptance:

Yet one would think that in a movement demanding acceptance, legalized marriage would be one of its primary issues. What a logical and convincing means of assuring society that they are sincere in wanting respect and dignity! But nowhere do we see this idea prominently displayed either in Society publications or the magazine ONE. It is dealt with in passing and dismissed as all-right-for-those-who-want-it. But it is not incorporated as a keystone in Society aims — which it must be before such a movement can hope for any success.

Saunders saw some practical problems that would need to be addressed if they were to press for gay marriage. Some of those problems were a reflection of the rigid gender roles that were still prevalent in the early 1950s. “For instance, should the Mr. And Mrs. Idea be retained? If so, what legal developments would come of the objection by the ‘Mr.’ that ‘Mrs.’ doesn’t contribute equally?” He wondered how childrearing and adoption would work. “Would the time come when homosexuals would be forced to care for children as part of their social duties? How many homosexuals would actually want to bring up a child?”

A Philadelphia gay wedding, ca 1957. This photograph was part of a set that was deemed inappropriate by a film processor in Philadelphia and never returned to the customer. From the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

Saunders saw the idea of two men or two women vowing to remain together, monogamously, for the rest of their lives “a dubious proposition.” Here again, he apparently hadn’t absorbed some of the statistics from the Kinsey report that found those expectations a dubious proposition for large numbers of heterosexual couples But he acknowledged that social pressure made for an additional and significant obstacle for gay couples. Those in a visible same-sex relationships risked arrest, eviction and unemployment, factors which tended to dampen the enthusiasm for such arrangements.

That’s why many of the early homophile activists saw sexual liberation as the only viable option. But that would be inimicable to the monogamous expectations of a homosexual marriage. “The concept of homosexual marriage cannot come into being without a companion idea: homosexual adultery,” with all of its societal and legal sanctions. For the sexual outlaws of 1953, would such a price for acceptance be worth it?

[T]his acceptance will cause as great a change in homosexual thinking as in the heterosexual — perhaps greater. No more sexual abandon: imagine! Me, married? Yes, a great change in the deviate himself, yet nothing in the literature of the Mattachine Society and little of ONE is devoted to initiating and exploring this idea of necessary homosexual monogamy. The idea seems stuffy and hide-bound. We simply don’t join movements to limit ourselves! Rebels such as we, demand freedom! But actually we have a greater freedom now (sub rosa as it may be) than do heterosexuals and any change will be to lose some of it in return for respectability. Are we willing to make the trade? From the silence of the Society on the subject, perhaps not.

What a turn! After challenging the homophile movement to embrace gay marriage in order to advance the cause of acceptance, he backtracks somewhat and indirectly questions whether gay people really knew what they wanted.

It is unfortunate that enthusiasm demands more action than thought, and that necessity often makes us run wildly before we’ve decided exactly where we’re running (although we may be quite sure of what we’re running from). Commendable as the Society is, it appears that there is yet to be conceived in its prospectus a concrete plan for the homosexual’s place in society. Until we know exactly where we’re going, and the stuffy and hide-bound — who can help us exceedingly — might not be willing to run along just for the exercise. When one digs, it must be to make a ditch, a well, a trench: something! Otherwise all of this energetic work merely produces a hole. Any bomb can do that.

The homophile movement did somehow manage to converge on a consensus, and that consensus leaned toward “just license” — or “liberation,” in the language of the next decade. Over the next several months, readers responded more or less that way in letters to ONE. One questioned the either/or proposition between the marriage license and “just license” by pointing to Scandinavia where “sex laws are sane, (heterosexual) marriage still exists, home is sacred, and mother is honored.” Another wondered why Saunders seemed intent on imposing restrictions rather than expanding options. “In the year 2053, he asks, are we to be allowed to continue our pursuit of physical happiness without restraint as we attempt to do today? Well, why the hell not? What is this tendency on the part of some people to seek more and more restrictions?” Another scoffed: “It seems preposterous to me to use a sexual behavior yardstick for present and future generations of homosexuals which does not even meet the needs and actions of most present day heterosexuals, much less their probable future needs. … I would also be for the legalized marriage of homosexuals who desire this. And, I am one who desires this. But, E.B.S.’s naiveté regarding heterosexual chastity before marriage astounds me.”

The homophile movement didn’t adopt Saunders’s call for gay marriage. It also came to realize that its plaintive pleas for “acceptance” and “understanding” of the 1950s would never produce the kind of changes they were looking for. By the time the decade ended, the push was on for license — liberation, in the lingo of the following decade — among gay activists like Frank Kameny (May 21) who demanded that the rights of gays and lesbians be respected solely because it was their birthright as citizens. By the time Stonewall came around, the lure of liberation made the idea of marriage seem irrelevant (although visionaries like Jack Baker and McConnell saw things differently (May 18)). But the AIDS tragedy of the 1980s had a way of injecting cold hard reality into the equation. There’s nothing like losing a partner to a terrible disease to focus one’s mind on all that was lost, and on all of the vulnerabilities — legal, financial, and social — that gay people were exposed to when they were denied access to marriage. The revolution may have picked up steam as the twentieth century began to draw to a close, but the seeds of discontent were already sown at least a half a century earlier.

[Sources: E.B. Saunders. “Reformers Choice: Marriage License or Just License?” ONE 1, no. 8 (August 1953): 10-12.

“Letters.” ONE 1, 10 (October 1953): 10-15.

“Letters.” ONE 1, 11 (November 1953): 18-24.]

Featured Reports

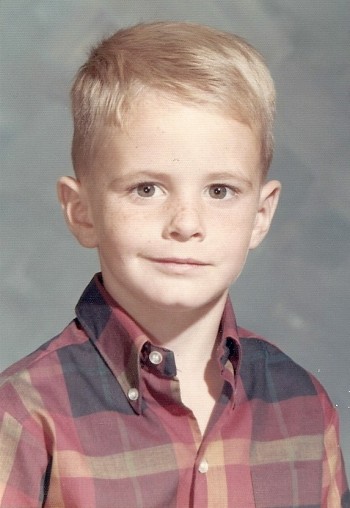

In this original BTB Investigation, we unveil the tragic story of Kirk Murphy, a four-year-old boy who was treated for “cross-gender disturbance” in 1970 by a young grad student by the name of George Rekers. This story is a stark reminder that there are severe and damaging consequences when therapists try to ensure that boys will be boys.

In this original BTB Investigation, we unveil the tragic story of Kirk Murphy, a four-year-old boy who was treated for “cross-gender disturbance” in 1970 by a young grad student by the name of George Rekers. This story is a stark reminder that there are severe and damaging consequences when therapists try to ensure that boys will be boys.

When we first reported on three American anti-gay activists traveling to Kampala for a three-day conference, we had no idea that it would be the first report of a long string of events leading to a proposal to institute the death penalty for LGBT people. But that is exactly what happened. In this report, we review our collection of more than 500 posts to tell the story of one nation’s embrace of hatred toward gay people. This report will be updated continuously as events continue to unfold. Check here for the latest updates.

In 2005, the Southern Poverty Law Center wrote that “[Paul] Cameron’s ‘science’ echoes Nazi Germany.” What the SPLC didn”t know was Cameron doesn’t just “echo” Nazi Germany. He quoted extensively from one of the Final Solution’s architects. This puts his fascination with quarantines, mandatory tattoos, and extermination being a “plausible idea” in a whole new and deeply disturbing light.

On February 10, I attended an all-day “Love Won Out” ex-gay conference in Phoenix, put on by Focus on the Family and Exodus International. In this series of reports, I talk about what I learned there: the people who go to these conferences, the things that they hear, and what this all means for them, their families and for the rest of us.

Prologue: Why I Went To “Love Won Out”

Part 1: What’s Love Got To Do With It?

Part 2: Parents Struggle With “No Exceptions”

Part 3: A Whole New Dialect

Part 4: It Depends On How The Meaning of the Word "Change" Changes

Part 5: A Candid Explanation For "Change"

At last, the truth can now be told.

At last, the truth can now be told.

Using the same research methods employed by most anti-gay political pressure groups, we examine the statistics and the case studies that dispel many of the myths about heterosexuality. Download your copy today!

And don‘t miss our companion report, How To Write An Anti-Gay Tract In Fifteen Easy Steps.

Anti-gay activists often charge that gay men and women pose a threat to children. In this report, we explore the supposed connection between homosexuality and child sexual abuse, the conclusions reached by the most knowledgeable professionals in the field, and how anti-gay activists continue to ignore their findings. This has tremendous consequences, not just for gay men and women, but more importantly for the safety of all our children.

Anti-gay activists often charge that gay men and women pose a threat to children. In this report, we explore the supposed connection between homosexuality and child sexual abuse, the conclusions reached by the most knowledgeable professionals in the field, and how anti-gay activists continue to ignore their findings. This has tremendous consequences, not just for gay men and women, but more importantly for the safety of all our children.

Anti-gay activists often cite the “Dutch Study” to claim that gay unions last only about 1½ years and that the these men have an average of eight additional partners per year outside of their steady relationship. In this report, we will take you step by step into the study to see whether the claims are true.

Tony Perkins’ Family Research Council submitted an Amicus Brief to the Maryland Court of Appeals as that court prepared to consider the issue of gay marriage. We examine just one small section of that brief to reveal the junk science and fraudulent claims of the Family “Research” Council.

The FBI’s annual Hate Crime Statistics aren’t as complete as they ought to be, and their report for 2004 was no exception. In fact, their most recent report has quite a few glaring holes. Holes big enough for Daniel Fetty to fall through.

The FBI’s annual Hate Crime Statistics aren’t as complete as they ought to be, and their report for 2004 was no exception. In fact, their most recent report has quite a few glaring holes. Holes big enough for Daniel Fetty to fall through.