Box Turtle Bulletin

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby News and commentary about the anti-gay lobby

News and commentary about the anti-gay lobbyPosts Tagged As: Anti-Homosexuality Bill

March 14th, 2012

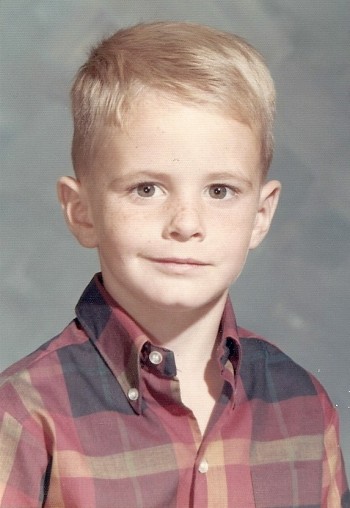

L-R: Unidentified woman, American holocaust revisionist Scott Lively, International Healing Foundation’s Caleb Brundidge, Exodus International boardmember Don Schmierer, Family Life Network (Uganda)’s Stephen Langa, at the time of the March 2009 anti-gay conference in Uganda.

The Center for Constitutional Rights has announced this morning that they are filing a lawsuit on behalf of Sexual Minorities of Uganda (SMUG) against American anti-gay extremist Scott Lively for his role in “the decade-long campaign he has waged, in coordination with his Ugandan counterparts, to persecute persons on the basis of their gender and/or sexual orientation and gender identity.” CCR announced its action this morning in a conference call with reporters. I was among those participating in the call.

The complaint (PDF: 2.2MB/47 pages) was filed in U.S. District Court in Massachusetts at Springfield, where Lively currently resides. CCR is bringing the suit under the Alien Tort Statute, which provides federal jurisdiction for “any civil action by an alien, for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” In other words, it allows a foreign national to sue in U.S. courts for violations of U.S. or international law conducted by U.S. citizens overseas. According to CCR, the U.S. Supreme Court has affirmed that ATS is a remedy for serious violations of international law norms that are “widely accepted and clearly defined.”

The crime against humanity in international law that CCR alleges that Lively violated is the crime of persecution, which is defined as the “intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of the identity of the group or collectivity.” CCR alleges that the defendant plaintif, Sexual Minorities Uganda, as well as individual staff members and member organizations, suffered severe deprivations of fundamental rights as a direct result of a coordinated campaign “largely initiated, instigated and directed” by Scott Lively.

In a conference call with reporters, CCR Senior Staff Attorney Pam Spees said that the Alien Tort Statute act had been applied in other specific cases of human rights violations against individuals. But she acknowledged that if this case prevails, it would establish a precedent for applying it to the crime of persecution, which, as a crime against a group, is different from a general “ordering the killing of people in his custody.” She pointed out U.S. asylum cases have acknowledged sexual orientation and gender identity and expression as legitimate claims for persecution.

Lively is best known for his role, reported first here on BTB, as featured speaker at an anti-gay conference held in Kampala in March 2009. During that conference, Lively touted his book, The Pink Swastika, in which he claimed that gays were responsible for founding the Nazi Party and running the gas chambers in the Holocaust. Lively then went on to blame the Rwandan genocide on gay men and he charged that gay people were flooding into Uganda from the West to recruit children into homosexuality via child sexual molestation.

During that same trip, Lively met with several members of Uganda’s Parliament. Only two weeks later, there were already rumors that Parliament was drafting a new law that “will be tough on homosexuals.” That new law, in its final form, would be introduced into Parliament later in October. Meanwhile, the public panic stoked by the March conference led to follow-up meetings, a march on Parliament, and a massive vigilante campaign waged on radio and the tabloid press. Lively would later boast that his March 2009 talk was a “nuclear bomb against the gay agenda in Uganda.”

In the complaint filed in Federal District Court, CCR provides details of Lively’s activities in Uganda going back to 2002, when Lively began touring Uganda and establishing contacts with leading Ugandan figures, including Stephen Langa (who organized the March 2009 conference) and Pentecostal pastor Martin Ssempa. While there, he was interviewed for major daily newspapers and appeared on radio and television. In a conference call with reporters, Spees said that Lively’s particular influence on Uganda’s religious leaders was the primary avenue for “telegraphing the sense of terror” through his accusations against the gay community, and that influence picked up significantly following the 2009 conference. The complaint includes several examples where Lively’s rhetoric showed up virtually verbatim in statements from Ugandan religious and political leaders. She also pointed out that the preamble of the bill’s original draft included language that was lifted straight out of conference materials.

Tarso LuÃs Ramos, Executive Director of Political Research Associates, echoed Spees’s assertion that Lively’s influence played a major role in the growing climate of persecution in Uganda. He described the main avenue of influence as from religious leaders like Lively to prominent Ugandan religious leaders who also wield considerable moral and political influence. Ramons said that during Lively’s 2009 trip to Uganda, he also met with members of the Ugandan Christian Lawyers Association and members of Parliament, and spoke at an assembly of 5,000 college students and at major pentecostal churches. According to the complaint, M.P. David Bahati, author of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, was among those who attended the Kampala conference. Bahati and former Ethics and Integrity Minister James Nsaba Buturo were also named as co-conspirators in the complaint.

Ramos and Spees contrasted Lively’s role with that of the secretive U.S. organization known as The Family or The Fellowship. Spees described Lively as the “go-to guy whose rhetoric went into hyperspace to stamp out” LGBT people “in a strategic way.” She alleged that he provided a “tangible, clear plan” in contrast to The Family, which tried to distance itself from the bill. One part of the “clear plan” outlined in the complaint was Lively’s recommendation for the criminalization of LGBT advocacy in Uganda. That recommendation became Clause 13 in the Anti-Homosexuality Bill.

Spees emphasized that while Lively’s “violent anti-gay rhetoric” forms a basis for the evidence of the complaint, the case is not about hate speech but what she described as his systematic efforts to provoke persecution in Uganda and elsewhere. She described Lively as a “key player in persecution” in a concerted effort to deprive and remove rights for LGBT Ugandans.

Speaking via telephone form Uganda, SMUG Executive Director Frank Mugisha welcomed the filing. He said that when the March 2009 Kampala conference was announced, they had no idea how far that conference’s influence would go. Before 2009, he described an atmosphere where people were somewhat freer to live in groups as gay people, but after the conference there were demonstrations, meetings, reports of arrests, people being thrown out of their houses and churches, beatings, and severe curbs on freedom of assembly. Just last month, Ugandan authorities raided a meeting by LGBT leaders at a hotel in Entebbe and tried to arrest Kasha Jacqueline Nabagese, founder of the lesbian rights group Freedom and Roam Uganda.

More information about the lawsuit against Lively can be found at the CCR web site.

Update: The New York Times has this reaction from Lively:

Reached by telephone in Springfield, Mass., where he now runs “Holy Grounds Coffee House,” a storefront mission and coffee shop, Mr. Lively said he had not been served and did not know about the lawsuit. However, he said: “That’s about as ridiculous as it gets. I’ve never done anything in Uganda except preach the Gospel and speak my opinion about the homosexual issue. There’s actually no grounds for litigation on this.”

March 2nd, 2012

Today’s edition of the Ugandan government-owned New Vision has published a statement from FIDA, the Ugandan Association of Women Lawyers, opposing the proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill. The statement says, in part:

[A]s a human rights organization we strongly oppose the proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill. In the first instance, human rights are in-born and belong to all individuals equally without requiring any permission for their enjoyment. Human rights are also not conferred by the State or by any other institution, organization or individual.

In the circumstances, we believe that the proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill is unnecessary and redundant. The current Criminal Law — particularly the Penal Code Amendment of 2007 — fully protects all children, whether boys or girls from sexual exploitation by any individual who may abuse his or her position of power or authority. Furthermore, the Penal Code Act already provides for the offences outlined in the Anti-Homosexuality Bill. Moreover, the Bill contains several clauses that cannot survive the many tests provided by the 1995 Constitution of Uganda. This is because the Bill violates, among others, the rights to equality and non-discrimination, privacy, as well as the freedoms of speech, expression, association and assembly.

Sexual relations between willing and consenting adults is a private affair which the State should not police. Attempting to enforce the proposed Bill would amount to a gross and unjustified intrusion into the lives and privacy of all people in Uganda, for it would require constant surveillance of all bedrooms to ascertain who is having sexual intercourse with whom and how.

The statement’s placement (PDF: 1.7MB/1 page) in the pro-government newspaper is on a page dedicated to news for the country’s significant Muslim minority. It is located under an article in which an Imam at Africa’s largest mosque in Kampala urges Muslim men to avoid the “vice” of homosexuality by taking four wives as allowed by Islam.

February 24th, 2012

Yet another journalist not getting his facts right in an otherwise good report:

Meanwhile, the anti-homosexuality legislation—with the death penalty clause removed—is working its way through a weeks-long hearing process.

No, no, a million times no!

Let’s go through this one more time!

It’s important to address the persistent false reports in the media that the death penalty has been removed from the bill. Those false reports have been reported as though they were fact since December, 2009. Part of the confusion has stemmed from the Ugandan governments’ pronouncements over the years that the bill has been “rejected”. In April 2010, that so-called “rejection” was followed by a government recommendation that the bill’s provisions be passed under the radar in other, less controversial bills. Additional reports of the government “shelving” the bill emerged in March 2011, only to be followed again a few weeks later with suggestions that the bill be carved up and passed unnoticed in other bills.

Finally in May of 2011, the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee, which had been charged with the task of coming up with recommendations for the bill, issued their final report. They recommended removing some clauses of the bill, while also recommending the addition of a new clause criminalizing the conduct of same-sex marriages. As for the death penalty provision, the committee recommended a sly change to the bill, removing the explicit language of “suffer(ing) death,” and replacing it with a reference to the penalties provided in an unrelated already existing law. That law however specifies the death penalty. Which means that the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee recommended that the death penalty be retained through stealth. Bahati then went on to claim that the death penalty was removed even though it was still a part of the bill. The Eighth Parliament ended before it could act on the committee’s recommendation.

On February 7, 2012, the original version of the bill, unchanged from when it was first introduced in 2009, was reintroduced into the Ninth Parliament. The bill was again sent to the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. Despite reports to the contrary, the original language specifying the death penalty is still in the bill, and will remain there unless the committee recommends its removal and Parliament adopts that recommendation in a floor vote.

We have been following this story closely for exactly three years now, and have covered all of the ins and outs of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill since its introduction in October 2009. So it’s not as if this information isn’t out there or difficult to find. Maybe someday journalists will get this right, but it doesn’t look like it’s happening anytime soon.

February 24th, 2012

This morning’s Daily Monitor, Uganda’s largest independent newspaper, reports that the Uganda Law Society has warned that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill would institutionalize discrimination against those “who are, or thought to be gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender.” The law group warned:

“The bill would further purport to criminalise the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality, compel HIV testing in certain circumstances, impose life sentences for entering into a same-sex marriage, introduce the death penalty for ‘aggravated’ homosexuality, as well as punish those who fail to report knowledge of any violations of its provisions within 24 hours,” said the ULS.

…Mr James Mukasa Sebugenyi, the ULS president, said the bill would violate rights to freedom of expression, thought, peaceful assembly, association, liberty and security of the person and privacy among others.

In a statement issued last week, ULS warned:

Generally, the bill would violate the principle of non-discrimination and would lead to violations of the human rights to freedom of expression, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of peaceful assembly, freedom of association, liberty and security of the person, privacy, the highest standard of health, and to life. These rights are guaranteed under the Constitution of Uganda and in international and regional treaties to which Uganda is party, which include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter).

The statement goes on to cite several articles of the Uganda Constitution which the proposed bill would violate.

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 24th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

A couple of the clauses in the Anti-Homosexuality Bill are administrative:

15. Jurisdiction.

Save for aggravated homosexuality that shall be tried by the High Court, the magistrates court shall have jurisdiction to try the other offences under this Act.

19. Regulations.

The Minister may, by statutory instrument, make regulations generally for better carrying out the provisions of this Act.

On first blush, both of these clauses look rather innocuous. Clause 15 sets out which courts will have jurisdiction over which portion of the bill. Uganda’s High Court hears the most serious cases, and Clause 1 gives it sole jurisdiction over “aggravated homosexuality” (Clause 3) which currently carries the death penalty under the proposed bill. Magistrate Courts generally sit below High Court in terms of the severity of criminal cases that they hear. As far as I know, it appears that Clause 15 is probably fairly typical given the kinds of penalties that would be under consideration.

Where Clause 15 is uninteresting, Clause 19 is something entirely alarming. Someone will be tasked to issue further regulations to ensure that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill is enforced. And who is that Minister charged with that task? To find out, you will need to find the definition in Clause 1:

“Minister'” means the Minister responsible for ethics and integrity;

In the current regime, that would be Ethics and Integrity Minister Simon Lokodo, a defrocked Catholic priest who last week led a group of armed guards in a raid of a hotel in Entebbe where a LGBT advocacy conference was taking place. He summarily ordered the arrest of LGBT advocate Kasha Jacqueline Nabageser, but Kasha slipped away and was able to avoid Lokodo’s thugs. If Lokodo could break up a meeting with no legal basis whatsoever, imagine the reign of terror he would engineer once he has the Anti-Homosexuality Bill with all of the opportunities for abuse it provides.

Lokodo’s predecessor, James Nsaba Buturo, also saw his office as enforcer-in-chief of Uganda’s particular brand of “ethics and integrity.” And he, like Lokodo, also saw himself as the nation’s pastor, writing lengthy op-eds in Ugandan newspapers intoning on the moral evils he saw plaguing the country. Before President Yoweri Museveni came to power in 1986 following a civil war, Buturo served in Milton Obote’s bloody regime as an enforcer who was adept at making Obote’s enemies disappear. In Museveni’s government, he wielded a softer touch, but was no less insistent in his goal of making gays disappear. While Buturo has apparently fallen out of favor with the Museveni government, having been forced to resign in early 2011, he set a pattern that Lokodo would emulate. In December 2010, Buturo banned the screening of a documentary film which depicted, in part, the work of LGBT human rights workers.

One senses that should the Anti-Homosexuality Bill becomes law, the Ministry of Ethics and Integrity could very well change its name to the Ugandan Inquisition. And why not? There are many parallels. An early draft of the bill included a paragraph in its accompanying memorandum extolling the virtues of ex-gay therapy. That paragraph was dropped when the bill was introduced into Parliament in 2009, but that didn’t stop the bill’s supporters to trot out a supposedly ex-gay person as a modern-day converso. And the witch-hunts which would be unleashed by Clause 14, the ban on all deviation from the Ugandan Inquisition via Clause 13, the startling ease with which someone could be put to death in Clause 3 with the High Court being put in charge of the auto-da-fé — these are the measures that Tomás de Torquemada himself would appreciate.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

February 23rd, 2012

In a New York Times blog post, Journalist Dayo Olobade sees Uganda’s LGBT community a convenitent diversion whenever government leaders have too many other problems to grapple with.

Last year, the government spent more than $500 million on new military planes while failing to build, staff or maintain maternity hospitals. This year, parliament approved payments of 103 million Ugandan shillings (about $45,000) per representative in order for each to buy a new car. A recent wave of influence-peddling scandals has left seven cabinet positions vacant. In this climate, it seems curious that (Ethics and Integrity Minister Simon) Lokodo, whose portfolio includes both “gay issues” and dealing with corruption in government, should invest such personal interest in the former and not the latter.

…The long-serving President Yoweri Museveni, meanwhile, has disavowed parliament’s activity both times the (Anti-Homosexuality) bill has been considered, primarily, it seems, out of fear that gay-bashing might endanger foreign aid from rights-conscious donors like the United States and Britain. That’s not to say he and his cohort don’t benefit from this culture-war sideshow: three days before Bahati’s bill resurfaced this month, the president signed a controversial new oil contract. Last year, after a series of opaque agreements with foreign companies, parliament had ruled that no new production-sharing agreements were to be signed until a comprehensive regulatory regime had been established. The president’s office, insisting that an engagement with the British energy company Tullow Oil pre-dated the moratorium, went ahead anyway.

“You’d think that the government, given pressure regarding the oil sector, would begin the legislative session with the oil reforms,” says Angelo Izama, an experienced Ugandan journalist on the oil beat. “But they began with the gay bill. It’s not accidental.” The semi-successful diversion, coupled with disregard for parliamentary procedures, illustrates the lack of checks on the behavior of the Museveni government.

Museveni, who has held power since winning a civil war in 1986, has spoken out against the bill. But it doesn’t take a political genius to see that he finds having the bill around benefits him politically. He elevated Lokodo, a defrocked Catholic priest, to his cabinet and Lokodo immediately set about raiding a workshop on LGBT advocacy. Museveni also undoubtedly had a hand in raising MP David Bahati, the Anti-Homosexuality Bill’s sponsor, to the position of acting chairman of the ruling party’s caucus in Parliament. It’s inconceivable that Bahati would have reached that position without Museveni’s solid support, and its very difficult to read that move as a reward for providing Museveni with a convenient diversion that he can use whenever he needs it.

Meanwhile, Museveni appeared in a BBC television interview to deny that gay people are being persecuted in Uganda. “Homosexuals — in small numbers — have existed in our part of black Africa. They were never prosecuted, they were never discriminated,” he told BBC’s Stephen Sackur just days after his government’s raid on Entebbe. Museveni made those comments during a visit to London to launch a tourism innitiativeand attend a summit on Somolia.

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 23rd, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

We’ve talked about Clause 14 twice before in this series. We described how the mandatory reporting clause is a threat to doctors, lawyers, social workers, pastors, and anyone else who “aids and abets” gay people (in conjunction with Clause 7) and how the law is a particular danger to landlords, friends and family members of gay people (in conjunction with Clause 11). But after having looked at the previous thirteen clauses in the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, with all of the crimes and all of the penalties that those clauses provide, let’s look at Clause 14 again, except this time I want to highlight something I’m not sure was noticed before (my apologies in advance to anyone who did notice what I’m about to talk about):

14. Failure to disclose the offence.

A person in authority, who being aware of the commission of any offence under this Act, omits to report the offence to the relevant authorities within twenty-four hours of having first had that knowledge, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty currency points or imprisonment not exceeding three years.

Did you catch it? Look again: “A person in authority, who being aware of the commission of any offence under this Act…”

Discussions about the Anti-Homosexuality Bill often talk about this clause as requiring anyone who knows someone who is gay being required to report that person to the police. But that’s not what this clause says. Well, it does say that, but it also says so much more.

What it says is that if anyone learns that a doctor is treating gay people, they are required to report that doctor to police within twenty-four hours for “aiding and abetting” homosexuality in violation of Clause 7, because Clause 7 is an “offence under this Act.” If someone learns of a landlord renting to gay people or a hotel owner renting a room to gay people, then that person is required to report the landlord or hotel owner to police within twenty-four hours for violating Clause 11, another “offence under this Act.” If someone learns of someone providing a safe house to gay people on the run, then that person is required to report the sanctuary-provider to police within twenty-four hours for also violating Clause 11. If someone learns of a person making donation to a gay-rights group, then that person is required to report the donor to police within twenty-four hours for violating Clause 13. If someone learns of anyone who says that gay rights should be respected, then that person is required to report the rights advocate to police within twenty-four hours for also violating Clause 13.

And that’s in addition to the case where someone learns that somebody else touched someone else’s “any part of the body” “with anything else” “through anything” in an act which “does not necessarily culminate in intercourse,” that that person is required to report that “toucher” to police for violating Clauses 1 and 2.

And if anyone should fail to report any of these things — and much more — within twenty-four hours of learning about it, that person could be thrown in prison for three years or fined five million shillings, which is about US$2,100 in a country where the per capita annual income is about US$500.

The extend of this reporting requirement is nearly endless.

When the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee issued its recommendations in the closing days of the Eighth Parliament, they recommended deleting Clause 14, saying “The offence will create absurdities and the provision will be too hard to implement.” Absurdities indeed. The Eighth Parliament ended before the committee’s recommendation could be adopted, and when the Anti-Homosexuality Bill was re-introduced into the Ninth Parliament, it was the original bill that was reintroduced with Clause 14 intact. The bill is again in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee for further consideration.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 22nd, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

The memorandum which serves as the preamble to the Anti-Homosexuality Bill makes clear that one of the aims of the bill is to prohibit “the promotion or recognition of such sexual relations in public institutions and other places through or with the support of any Government entity in Uganda or any non governmental organization inside or outside the country.” Clause 13 is where the bill tries to achieve that aim:

13. Promotion of homosexuality.

(1) A person who –(a) participates in production, procuring, marketing, broadcasting, disseminating, publishing pornographic materials for purposes of promoting homosexuality;

(b) funds or sponsors homosexuality or other related activities;

(c) offers premises and other related fixed or movable assets for purposes of homosexuality or promoting homosexuality;

(d) uses electronic devices which include internet, films, mobile phones for purposes of homosexuality or promoting homosexuality and;

(e) who acts as an accomplice or attempts to promote or in any way abets homosexuality and related practices;

commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a line of five thousand currency points or imprisonment of a minimum of five years and a maximum of seven years or both fine and imprisonment.

(2) Where the offender is a corporate body or a business or an association or a non-governmental organization, on conviction its certificate of registration shall be cancelled and the director or proprietor or promoter shall be liable on conviction to imprisonment for seven years.

This bill would thoroughly outlaw any and all advocacy on gay rights in Uganda. Subclause 1.a speaks of “pornographic materials,” implying a limited scope of the bill. But in reality, even the most innocuous depictions or descriptions of LGBT people have been condemned as “pornographic.” The remaining clauses have no similar pretense of restraint. Sublcause 1.b prohibits all funding for LGBT advocacy, 1.c prohibits any property or assets from being used for LGBT advocacy, and 1.d prohibits all electronic media, including the Internet, Emails, SMS text messages, YouTube videos and anything else you can think of that can be used to argue for LGBT rights. This clause bans everything: blog posts, Facebook status updates, even a 140-character Tweet can land the Tweeter in prison for up to seven years.

And in case the bill’s authors forgot anything, subclause 1.e is there as a catch-all for any other possible avenues for advocating on behalf of gay people. This covers any kind of advocacy including, potentially, legal defense for anyone charged under this bill, and even any future parliamentary debate over whether sections of this bill should be amended or repealed. In fact, this clause is redundant with Clause 7 which prohibits “Aiding and Abetting” homosexuality (which the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee recommended deleting in favor of this clause). Which means that all of the dangers that Clause 7 poses to lawyers, health care workers, counsellors, pastors — even beauticians (is making a gay person attractive “aiding and abetting” homosexuality?) — apply to this clause as well.

Subclause 1 provides a sentence of five to seven years imprisonment for an individual, and a fine of 100 million shillings, or about US$42,500 in a country where the per capita annual income is about US$500. Businesses, non-profits and NGO’s aren’t exempt either; the law shuts them down and imprisons their directors or owners for seven years.

In a human rights forum discussing the Anti-Homosexuality Bill held at Makarere University in 2009, law professor Sylvia Tamale describes just some of the dangers Clause 13 poses:

Clause 13 which attempts to outlaw the “Promotion of Homosexuality” is very problematic as it introduces widespread censorship and undermines fundamental freedoms such as the rights to free speech, expression, association and assembly. Under this provision an unscrupulous person aspiring to unseat a member of parliament can easily send the incumbent MP unsolicited material via e-mail or text messaging, implicating the latter as one “promoting homosexuality.” After being framed in that way, it will be very difficult for the victim to shake free of the “stigma.” Secondly, by criminalizing the “funding and sponsoring of homosexuality and related activities,” the bill deals a major blow to Uganda’s public health policies and efforts. Take for example, the Most At Risk Populations’ Initiative (MARPI) introduced by the Ministry of Health in 2008, which targets specific populations in a comprehensive manner to curb the HIV/AIDS scourge. If this bill becomes law, health practitioners as well as those that have put money into this exemplary initiative will automatically be liable to imprisonment for seven years! The clause further undermines civil society activities by threatening the fundamental rights of NGOs and the use of intimidating tactics to shackle their directors and managers.

In addition to the likelihood that Clause 13 could be abused for criminal or political purposes, the provisions in Clause 13 violate Uganda’s constitution (PDF: 460KB/192 pages), which under Chapter 4, Article 29, (Pages 41-42) include:

29. Protection of freedom of conscience, expression, movement, religion, assembly and association.

(1) Every person shall have the right to—(a) freedom of speech and expression which shall include freedom of the press and other media;

(b) freedom of thought, conscience and belief which shall include academic freedom in institutions of learning;

(c) freedom to practise any religion and manifest such practice which shall include the right to belong to and participate in the practices of any religious body or organisation in a manner consistent with this Constitution;

(d) freedom to assemble and to demonstrate together with others peacefully and unarmed and to petition; and

(e) freedom of association which shall include the freedom to form and join associations or unions, including trade unions and political and other civic organisations.

The adoption of this clause would make a mockery of Uganda’s constitution. Nevertheless, the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee recommended retaining Clause 13 in its entirety in the closing days of the Eighth Parliament, and it remained as part of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill when it was reintroduced into the Ninth Parliament.

In the film The Silence of the Lambs, the evil Hannibal Lecter asked detective Clarice Starling what her most painful memory was. She replied with a story about living on a relative’s farm near a slaughterhouse where she tried unsuccessfully to rescue one of the lambs. She was haunted by the screaming the lambs made as they were being slaughtered. Lecter later asks Starling, “Tell me, Clarice, have the lambs stopped screaming?” This clause, as part of a bill designed to legislate LGBT people out of existence, will ensure that no one is allowed to hear them scream.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 21st, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

In the bill’s memorandum which serves as a prologue, it gives as the bill’s first objective as “provid(ing) for marriage in Uganda as that contracted only between a man and a woman,” but it waits until Clause 12 before finally banning it. What’s more, it doesn’t just ban same-sex marriage, it specifies a criminal penalty for it:

12. Same sex marriage.

A person who purports to contract a marriage with another person of the same sex commits the offence of homosexuality and shall be liable on conviction to imprisonment for life.

In more than half of the states of the U.S., same-sex marriage is banned, as it is in most other parts of the world. Where it is banned, nearly every other jurisdiction is satisfied to simply make such an arrangement a legal impossibility. But it is an exceptionally rare country (is there another one?) that goes so far as turning marriage into a criminal offense, let alone one such as Uganda that carries a penalty of a lifetime in prison. And yet, that is exactly what this bill would do. Any Ugandan who presents another person of the same sex as a spouse has broken a law so severe that the individual would be cast for the rest of his or her life into a Ugandan prison.

But not only that, it would appear possible that with the clause beginning with “a person who purports to contract a marriage…” might endanger any foreign married visitor who enters Uganda, either as a business person or a tourist, who mentions his or her same-sex spouse to anyone in Uganda.

Yet with all that, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee felt that the clause didn’t go far enough. They recommended the addition of a second subclause:

2) A person or institution commits an offence if that person or institution conducts a marriage ceremony between persons of the same sex and shall on conviction be liable to imprisonment to a maximum of three years for individuals or cancellation of licence for an institution.”

With this provision, a minister in a denomination or religion that recognizes same-sex marriage could be imprisoned for practicing that denomination’s religious beliefs. Both of these provisions together run counter to Uganda’s own constitution (PDF: 460KB/192 pages), which under Chapter 4, Article 29, (Page 42) includes the following:

(1) Every person shall have the right to—

…(c) freedom to practise any religion and manifest such practice which shall include the right to belong to and participate in the practices of any religious body or organisation in a manner consistent with this Constitution;

So much for religious freedom in Uganda.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause by Clause with the Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 20th, 2012

The proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill, 2009. (Click to download, PDF: 847KB/16 pages)

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

As we’ve seen so far in this series examining Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill, the dangers that this bill poses extend far, far beyond the gay community itself. It threatens anyone who in any way come in contact (even literally) with gay people. Clause 11 provides yet another danger this bill would pose to just about anyone:

11. Brothels.

(1) A person who keeps a house, room,set of rooms or place of any kind for the purposes of homosexuality commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for seven years.2) A person being the owner or occupier of premises or having or acting or assisting in the management or control of the premises, induces or knowingly suffers any man or woman to resort to or be upon such premises for the purpose of being unlawfully and carnally known by any man or woman of the same sex whether such carnal knowledge is intended to be with any particular man or woman generally, commits a felony and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for five years.

The title of the clause names brothels, ordinarily understood as houses of ill-repute, places of prostitution. But the subclauses below it suggest nothing of the kind. They don’t mention prostitution, making money from sex, charging money for sex, arranging or accommodating for sex-for-pay, or anything else that one might associate with running a brothel. But among the things this clause does prohibit is renting a home, a room or even lending a spare bed to anyone who is gay. That act would expose them to the danger of being imprisoned for ether five or seven years, depending on how the police and prosecution decide to press charges. Homeowners, landlords, hotel owners, hostel operators, or just someone (even a relative) offering guest accommodations to gay visitors can find themselves in trouble with the law. In the worst possible scenario, this clause could also be used to prosecute those who provide safe houses for gay Ugandans who are in hiding for their own safety.

If the goal of this bill is to drive all LGBT Ugandans out of the country, this clause alone would be one way to do it. After all, if it becomes impossible to find a place to live because the property owner could be jailed if authorities found out you were gay, where could you go? Back home to your family? Think again:

14. Failure to disclose the offence.

A person in authority, who being aware of the commission of any offence under this Act, omits to report the offence to the relevant authorities within twenty-four hours of having first had that knowledge, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty currency points or imprisonment not exceeding three years.

Clause 1 defines “authority” this way:

“authority” means having power and control over other people because of your knowledge and official position; and shall include a person who exercises religious. political, economic or social authority;

Again, it’s the definition’s broadness which invites trouble. Because of the “social authority” invested by Ugandan society in family ties, relatives fall under the requirement to report their loved ones to police within twenty-four hours of discovering they were gay. As Makarere University Law Professor Sylvia Tamale pointed out during a public debate on the bill in 2009:

The bill requires family members to “spy” on one another. This provision obviously does not strengthen the family unit in the manner that Hon. Bahati claims his bill wants to do, but rather promotes the breaking up of the family. This provision further threatens relationships beyond family members. What do I mean? If a gay person talks to his priest or his doctor in confidence, seeking advice, the bill requires that such person breaches their trust and confidentiality with the gay individual and immediately hands them over to the police within 24 hours. Failure to do so draws the risk of arrest to themselves. Or a mother who is trying to come to terms with her child’s sexual orientation may be dragged to police cells for not turning in her child to the authorities. The same fate would befall teachers, priests, local councilors, counselors, doctors, landlords, elders, employers, MPs, lawyers, etc.

She also points out that this clause opens up family members to potential abuse, blackmail and extortion. Logic would have it that if family members could be blackmailed, then landlords and hotel owners could also fall prey. Pay up, or we’ll report you along with the gay people you’re harboring.

So, you can’t rent a home, you can’t return to your family, what’s next? Go abroad?

16. Extra- Territorial Jurisdiction.

This Act shall apply to offenses committed outside Uganda where –(a) a person who, while being a citizen of or permanently residing in Uganda, commits an act outside Uganda, which act would constitute an offence under this Act had it been committed in Uganda; or

(b) the offence was committed partly outside and or partly in Uganda.

17. Extradition.

A person charged with an offence under this Act shall be liable to extradition under the existing extradition laws.

That’s right. Uganda reserves the right to prosecute Ugandans living abroad with crimes under the Anti-Homosexuality Bill. Extradition is normally reserved for the most serious felonies — murder, kidnapping, robbery, extortion, etc. It’s likely that very few nations would extradite a gay Ugandan from their borders. But many nations have deported Ugandans back to their home country after denying them asylum. Gay Ugandans in this scenario, even if they had been squeaky-clean back home, could be charged for anything they had done outside of Uganda.

(The scope of clauses 16 and 17 are so broad that we will return to them again later in this series.)

When the bill went to the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee during the Eighth Parliament, they recommended keeping Clause 11. But they found Clause 14 “will create absurdities and the provision will be too hard to implement.” They recommended deleting Clause 14, along with Clauses 16 and 17, of which they said “the practical enforcement and implementation of the provision will be difficult.” But the Eighth Parliament ended before the committee’s recommendations could be accepted in a floor vote. The original bill, which was reintroduced earlier this month into the Ninth Parliament, is back in the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee for further consideration. And with it, these four clauses are again under scrutiny.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 16th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

After having examined the many ways in which just about anyone can be charged with homosexuality, the many ways in which just about anyone can earn the death sentence, the ridiculous clause against “attempted homosexuality” (when the burden of proof for the “crime” of homosexuality is set so low that it’s almost impossible how anyone could stop short at “attempting it”), and the dangers that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill pose to doctors, lawyers, beauticians, and just about everyone else who comes in contact with gay people — you’d think after all that, we’d be just about finished with examining the Anti-Homoseuxality Bill.

Unfortunately, we are only now reaching the half-way point. So let’s continue and dispense with these three clauses quickly:

8. Conspiracy to engage in homosexuality.

A person who conspires with another to induce another person of the same sex by any means of false pretence or other fraudulent means to permit any person of the same sex to have unlawful carnal knowledge of him or her commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for seven years.9. Procuring homosexuality by threats, etc.

(1) A person who–(a) by threats or intimidation procures or attempts to procure any woman or man to have any unlawful carnal knowledge with any person of the same sex, either in Uganda or elsewhere;

(b) by false pretences or false representations procures any woman or man to have any unlawful carnal connection with any person of the same sex, either in Uganda or elsewhere; or

(2) A person shall not be convicted of an offence under this section upon the evidence of one witness only, unless that witness is corroborated in some material particular by evidence implicating the accused.

10. Detention with intent to commit homosexuality.

A person who detains another person with the intention to commit acts of homosexuality with him or herself or with any other person commits an offence and is liable on conviction for seven years.

As is the case with the other clauses we’ve examined, these clauses are predicated on the assumption that there is no such thing as a consensual relationship as far as gay people are concerned. Someone is either a perpetrator or a victim, and if one is a victim, one is either “tricked” into homosexuality (how on earth does that happen?), is threatened into it, or is detained and forced into it. Clause 8, of course, is ridiculous, so much so that the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee recommended its deletion. But not because it’s nonsense, but because they somehow managed to find it redundant with Clause 13 (prohibiting the “promotion” of homosexuality) without explaining how it is redundant.

Clauses 9 and 10 however are somewhat more serious. After all, I think we can agree that threatening someone to have gay sex should be a crime, and that detaining someone in order to have gay sex with them should also be a crime. On those points, I think we all can find common ground.

But while we’re on the topic, shouldn’t threatening someone to have any kind of sex also be a crime? Shouldn’t detaining someone in order to have any kind of sex also be a crime? Of course they should be, and of course they already are.

The addition of these clauses here in the Anti-Homosexuality Bill serve no legal purpose. They merely make illegal that which is already illegal. But they do serve a propaganda purpose by reinforcing the idea that gay people are inherently criminal in all aspects of their relationships. And they also provide a convenient menu from which quick-thinking so-called “victims of homosexuality” can choose when they decide to take advantage of Clauses 5 and 6 to get out of jail free while throwing their partner under the bus.

As for the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee recommendations, they chose to keep Clause 10, but recognized that Clause 9 could have benefited from some proofreading. They recommended striking the unfinished phrase “either in Uganda or elsewhere; or” and adding at the end of the provision the words “…commits an offence and is liable on conviction be liable to imprisonment of seven years.” Oops. It looks like their recommendation needed some more proofreading.

As we said before, the Eight Parliament disbanded before adopting the recommendations. The bill that is back in the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee for the Ninth Parliament is the original bill, which still contains these clauses as originally submitted.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 16th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

As we have seen already in just the first six clauses of the proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill, it would be easy for anyone, gay or straight, to be caught up on charges which can bring either a lifetime prison sentence or the death penalty. Those clauses ostensibly target gay people, but the (possibly) unintended consequences of the sloppily-worded bill would also make heterosexuals vulnerable, particularly in a country where corruption is endemic. While those clauses supposedly target gay people, other clauses of the bill would target anyone, gay or straight, who would come to their aid. Like these clauses:

7. Aiding and abating (sic) homosexuality

A person who aids, abets, counsels or procures another to engage in acts of homosexuality commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for seven years.

14. Failure to disclose the offence.

A person in authority, who being aware of the commission of any offence under this Act, omits to report the offence to the relevant authorities within twenty-four hours of having first had that knowledge, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty currency points or imprisonment not exceeding three years.

The simple wording of these two clauses provides a breathtaking potential for all sorts of abuse. A straightforward reading of these clauses would leave doctors, lawyers, and other professionals vulnerable for providing services to gay people. That appears to be the precise aim of this bill, according to the British medical journal The Lancet, which reported in December of 2009 of a talk that M.P. David Bahati, the bill’s sponsor, gave before a cheering audience at Makerere University in Kampala (subscription required):

Before ceding the podium, Bahati had one last point to make. “This is not a Ugandan thing”, he said, his chest swelling with indignation. “Homosexuals are using foreign aid organisations to promote this. If an organisation is found to be promoting homosexuality, then their licence should be revoked.”

Shoulder to shoulder with Bahati’s supporters a half dozen or so Ugandans listened quietly. Several were doctors who had spent much of their careers toiling against a disease that has taken the lives of more than a million Ugandans. Their faces were stoic as they contemplated the implications of Bahati’s bill for the fight against HIV/AIDS not just among gay men but also among the wives and children of men who also have sex with men. They considered the long, lean years that had been spent quietly setting up networks to disburse information on HIV/AIDS to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex Ugandans.

“As a doctor, the law infuriates me”, said one general practitioner, who is much sought after by sexual minorities for his willingness to treat them, and who asked that his name not be used for fear that he would be arrested for working with sexual minorities. “We are only now getting to a point where people understand there is a problem. This law is going to erase all of that.”

It will erase all that for two reasons. Doctors who are found providing accurate safe-sex information to people who they know are gay can be held liable for “aiding and abetting” homosexuality. And gay people, understanding that Clause 14 would require doctors to report known gay people to police, would be driven underground. This is critical in the fight against AIDS. As The Lancet’s Zoe Alsop reported, in much of Africa, where AIDS is predominantly a heterosexual disease, many people, including doctors, believe that it’s impossible for gay people to become infected with HIV. This is a very different understanding than in the west.

Doctors aren’t the only professionals whose normal lines of work would make them susceptible to these two clauses. Counsellors and mental health professionals would also be susceptible, as would Lawyers who provide legal assistance or advice to gays and lesbians. Even pastors, whether they be pro-gay, anti-gay or neutral, could also find themselves held liable under these clauses.

But the dangers that these two clauses pose go way beyond the professions. Ordinary people who come in contact with LGBT people — whether they be friends, parents, siblings, co-workers, employers or neighbors — through ordinary kindnesses, accommodations, mutual aid and support, can be seen as “aiding and abetting” homosexuality. And they, too, could face imprisonment if they fail to report their gay friends, sons or daughters, brothers or sisters, co-workers, employees, or neighbors to police within twenty-four hours of finding out about that person’s sexuality.

The Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee, which reviewed the Anti-Homosexuality Bill during the closing days of the Eighth Parliament, recommended that Clause 7 against “aiding and abetting homosexuality” be deleted because, the committee said, it was covered by Clause 13 prohibiting the “promotion of homosexuality.” (We will examine that clause later.) As for Clause 14 requiring everyone to report gay people to police within twenty-four hours, the committee also recommended its deletion, saying “The offence will create absurdities and the provision will be too hard to implement.” The Eighth Parliament ended before the Committee’s recommendations could be accepted in a floor vote. The original bill, which was reintroduced into the Ninth Parliament, is back in the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee for further consideration. And with it, these two clauses are still being considered as well.

(Because Clause 14 is so breathtaking in its scope, I will discuss it further in a later installment.)

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause By Clause With Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 15th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

If you’ve been paying attention to the clauses we’ve examined so far, you may have noticed that the proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill tries to divide the gay world between aggressors and victims. Clauses 5 and 6 detail how “victims” are to be treated under the law:

5. Protection, assistance and payment of compensation to victims of homosexuality.

(1 ) A victim of homosexuality shall not be penalized for any crime commuted as a direct result of his or her involvement in homosexuality.(2) A victim of homosexuality shall be assisted to enable his or her views and concerns to be presented and considered at the appropriate stages of the criminal proceedings.

(3) Where a person is convicted of homosexuality or aggravated homosexuality under sections 2 and 3 of this Act, the court may, in addition to any sentence imposed on the offender, order that the victim of the offence be paid compensation by the offender for any physical, sexual or psychological harm caused to the victim by the offence.

(4) The amount of compensation shall be determined by the court and the court shall take into account the extent of harm suffered by the victim of the offence. the degree of force used by the offender and medical and other expenses incurred by the victim as a result of the offence.

6. Confidentiality.

(1) At any stage of the Investigation or trial of an offence under this Act, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, judicial officers and medical practitioners, as well as parties to the case, shall recognize the right to privacy of the victim.(2) For the purpose of subsection (1), in cases involving children and other cases where the court considers it appropriate. proceedings of the court shall be conducted in camera, outside the presence of the media.

(3) Any editor or publisher, reporter or columnist in case of printed materials. announcer or producer in case of television and radio, producer or director of a film to case of the movie industry, or any person utilizing trimedia facilities or information technology who publishes or causes the publicity of the names and personal circumstances or any other information tending to establish the victim’s identity without authority of court commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty currency points.

(Note: 1 currency point is 20,000 Ugandan shillings, or about US$8.60)

From the very first statement of clause 5, it becomes immediately obvious that this is a huge get-out-of-jail free card for anyone who is caught in the act of same-sex relations (or, as we have pointed out before, perhaps simply in the act of “touching” “any part of of the body” “with anything else” “through anything” in an act that “does not necessarily culminate in intercourse”) and quick enough to be the first to claim that he or she is a “victim.” Say, for example, if police should burst into your bedroom while you are there with another person of the same sex, and you are caught red-handed being handled “through anything” in an act that “does not necessarily culminate in intercourse,” all you have to do is claim to be the victim, that the other person made you do it, and right away you are free from prosecution.

Not only that, but they’ll help you testify in trial that, yep, sure enough, you were the victim, not the perpetrator. Not only will you escape a lifetime in prison — or even the hangman’s noose — but you will be awarded compensation for all of your trouble.

In other words, this provision is an open invitation for anyone to try to escape serious trouble by claiming to be a victim in the whole mess, no matter how much consent or how little actual sex took place. And come to think of it, these clauses are more than just open invitations, they practically beg one partner to rat out the other, and through the compensation clause, the law will literally pay them for doing so. And the bill offers the perfect escape hatch for the quick-witted or the well-connected: no one even needs to know that you were involved because the confidentially clause will ensure that your name stays out of the papers and television.

Bribe-taking throughout Uganda’s police and legal system is notorious, and the opportunities are rife for these two clauses to be abused in order to secure a conviction — as well as to let off scott-free anyone who may be in a privileged position to bribe or otherwise convince prosecutors into determining that they were the “victims.”

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause by Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 14th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

The next clause in Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill is Clause 4:

4. Attempt to commit homosexuality.

(1) A person who attempts to commit the offence of homosexuality commits a felony and is liable on conviction to imprisonment seven years.(2) A person who attempts to commit the offence of aggravated homosexuality commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for life.

After having dealt with Clauses 1 and 2 (which sets up the “crime” of homosexuality) and Clause 3 (the infamous death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality”), I hardly know what do do with this one. Particularly in light of the extraordinarily broad definition of the “crime” of homosexuality in Clauses 1 and 2 — where the crime of “touching” “any part of of the body” “with anything else” (a finger? an elbow? a Ronco Pocket Fisherman?) “through anything” in an act that does “not necessarily culminate in intercourse” can land you a lifetime in a Ugandan prison. Given that, it’s hard to know how someone can simply “attempt” to “touch” “any part of of the body” “with anything else” “through anything” without “culminat(ing) in intercourse” in a way that lands you seven years in prison. Or for life if you do all of that while HIV-positive.

Can you imagine the prosecutor in a case like this?

“Your honor, the defendant did maliciously and willfully attempt to touch another man’s shoulder with his kneecap through his jeans and the victim’s hoodie without culminating in intercourse, but failed to complete the attempt. The State demands seven years!”

“Beg your pardon Your Honor. The man whose shoulder he attempted to touch (but didn’t) with his kneecap through his jeans and the victim’s hoodie without culminating in intercourse, is missing a leg. That’s ‘attempted aggravated homosexuality’! The State demands life!”

In an extraordinarily rare spasm of legislative wisdom, Uganda’s Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee appears to have thought the better of this provision. According to a Human Rights Watch report, “the committee states that provisions criminalizing ‘attempted’ homosexuality should be removed, rightly stating such allegations would be very difficult to prove.” However, the Eighth Parliament closed before the legislature could act on the committee’s recommendations. As of last week, when the original bill was reintroduced in Parliament, this nonsensical provision was reintroduced with the rest.

Clause By Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill:

Clauses 1 and 2: Anybody Can Be Gay

Clause 3: Anyone Can Be “Liable To Suffer Death”

Clause 4: Anyone Can “Attempt to Commit Homosexuality”

Clauses 5 and 6: Anyone Can Be A Victim (And Get Out Of Jail Free If You Act Fast)

Clauses 7 and 14: Anyone Can “Aid And Abet”

Clauses 8 to 10: A Handy Menu For “Victims” To Choose From

Clauses 11, 14, 16 and 17: Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide

Clause 12: Till Life Imprisonment Do You Part

Clause 13: The Silencing of the Lambs

Clause 14: The Requirement Isn’t Only To Report Gay People To Police. It’s To Report Everyone.

Clauses 15 and 19: The Establishment Clauses For The Ugandan Inquisition

Clause by Clause With Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill

February 14th, 2012

Uganda’s proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill has been re-introduced into Parliament and is currently in the hands of the Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee. As the Committee considers what to do with the bill, there has been considerable confusion over what would happen if the bill were to become law. Most of the attention has focused on the bill’s death penalty provision, but even if it were removed, the bill’s other seventeen clauses would still represent a barbaric regression for Uganda’s human rights record. In this series, we will examine the original text of bill’s eighteen clauses to uncover exactly what it includes in its present form.

Today we examine the most discussed clause of the bill, Clause 3 which would establish the crime of “aggravated homosexuality”:

3. Aggravated homosexuality.

(1) A person commits the offense of aggravated homosexuality where the(a) person against whom the offence is committed is below the age of 18 years;

(b) offender is a person living with HIV;

(c) offender is a parent or guardian of the person against whom the offence is committed;

(d) offender is a person in authority over the person against whom the offence is committed;

(e) victim of the offence is a person with disability;

(f) offender is a serial offender, or

(g) offender applies, administers or causes to be used by any man or woman any drug, matter or thing with intent to stupefy overpower him or her so as to there by enable any person to have unlawful carnal connection with any person of the same sex,

(2) A person who commits the offence of aggravated homosexuality shall be liable on conviction to suffer death.

(3) Where a person is charged with the offence under this section, that person shall undergo a medical examination to ascertain his or her HIV status.

This is easily the most contentious clause of the bill, and the clause which the bill’s sponsor, M.P. David Bahati, has exploited to maximum effect. Go back and look at most of the definitions for “aggravated homosexuality” and see if you don’t agree with me that many of them represent some very horrendous crimes. Sex with minors? Check. Incest? Check. Slipping a Mickey? Check. Applying the death penalty to those provisions could be very contentious, but who among us haven’t reacted with the wish to “string them up” a few times in our lives?

But mixed in with those “crimes” are others which, on second look, demonstrate exactly what the bill’s author and supporters think of gay people. Take the provision where the “offender is a person living with HIV,” and notice that it is followed by a requirement that the suspect undergo an HIV test to ascertain his or her eligibility for the death sentence. In other words, whether the person knew he or she was HIV-positive is irrelevant in the bill. The government will find that out and decide whether the suspect qualifies for the death penalty. Additionally, there is nothing in the bill about whether the person tried to hide his or her HIV status. No matter whatever disclosures the individual may have made, no matter whatever precautions may have been taken, no matter whatever consent the suspect’s partner may have given — and no matter whether sex had actually occurred (See clauses 1 and 2) — an individual merits death according to this law simply for being HIV-positive. No matter what.

Another provision, where the “victim of the offence is a person with disability,” plays on the assumption built into the proposed law that the “offender” is predatory, which necessarily involves a “victim.” (We’ll discuss more on that later when we get to Clauses 5 and 6.) It also assumes that the person with the disability is unable to be an equal partner in a relationship. One couple that I know personally consists of a deaf man and a hearing man. They’ve been together for years, but under the terms of this bill, one would die while the other would go to prison for the rest of his life (unless he took advantage of Clauses 5 and 6).

But the worst part of this clause is where it lays the charge of “aggravated homosexuality” for when the “offender is a serial offender.” This clause alone can entangle almost anyone in the hangman’s noose. It all goes back to Clause 1, where you will find this definition:

“serial offender” means a person who has previous convictions of the offence of homosexuality or related offences; [emphasis mine]

There are a ton of “related offenses” in the proposed bill, including renting a room to a gay person, refusing to report a gay person to police, using the internet to advocate for the rights of gay people, donating to a pro-gay cause — and all of these offenses may be committed by straight people. A prior conviction on one of those clauses and then “touching” someone “with a part of a body” and “through anything” without anything even close to sex taking place (again, see clauses 1 and 2), and you’re headed to the gallows under this bill. Rob Tisinai illustrated how this can happen in this video from 2010.

The other provisions under this clause — those parts outlawing incest, child abuse, drugging someone — are already illegal under Ugandan law. This bill provides nothing new for those cases except for the death penalty. But those provisions are included in this bill for a very important reason: they provide a fig-leaf of an excuse for the bill which Bahati and his supporters have exploited to the fullest extent. For example, he told the BBC in December 2010:

There has been a distortion in the media that we are providing death for gays. That is not true,” he said. “When a homosexual defiles a kid of less than 18 years old, we are providing a penalty for this.”

Two days later, he told The Guardian:

The section of the death penalty relates to defilement by an adult who is homosexual and this is consistent with the law on defilement which was passed in 2007. The whole intention is to prevent the recruitment of under-age children, which is going on in single-sex schools. We must stop the recruitment and secure the future of our children.”

On December 27, he went on Ugandan television to say: